The project Sianëtsio sikowa’i “Amazonía Siempre Conectada,” jointly carried out by the Laboratorio Popular de Medios Libres (LPML) and CEFO Indígena with funding from the Internet Society Foundation (ISOC Foundation), represents one of the most significant efforts in recent years toward building autonomous community networks in the Amazon. Its most visible outcome was the installation of six community internet networks in the Siekopaai Nation, located in the Putumayo basin. However, the true value of this experience lies in the processes that shaped it: the selection of technical solutions adapted to the context, the definition of a sustainable economic model, and the implementation of a pedagogical methodology that acknowledges and strengthens local knowledge.

The starting point was the recognition that access to the internet in Amazonian territories faces structural obstacles. Dispersed geography, reliance on solar systems for electricity supply, lack of state infrastructure, and the high costs of satellite connectivity make the region historically marginalized. In this scenario, the project did not aim to “bring internet” as if it were an external package, but rather to build technological sovereignty based on accumulated experience from other community processes in Latin America, rooted in the needs and decisions of the Amazonian peoples themselves.

The LPML approached this initiative with more than a decade of work in rural and Indigenous territories. Processes such as those in Xochiteopan in Puebla and Tututepec in Oaxaca (México) had demonstrated that it was possible to design and implement sustainable community networks when three dimensions were combined: a robust technical architecture, a community-based economic model, and a pedagogy that trained local technicians. With these premises, Sianëtsio sikowa’i “Amazonía Siempre Conectada” was conceived as a comprehensive project rather than a simple technical intervention.

The first component was technical selection. Far from adopting standardized solutions, the team relied on a systematization of previous experiences to choose equipment and configurations capable of operating in Amazonian conditions, characterized by extreme humidity, constant rainfall, and high temperatures. The process also included criteria such as low energy consumption, compatibility with solar systems, ease of operation after short trainings, and the availability of spare parts in regional markets in Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru. The network topology was designed based on the geography of the Siekopaai territory, with communities separated by rivers and dense forest areas. Initially, configurations with multiple antenna sectors at each node were proposed, but during installation the design was adjusted to reduce redundancies and optimize energy consumption. This principle of situated adaptation, in which the technical plan is adjusted to the real context rather than imposing a rigid model, is one of the central lessons of the experience. Technology does not dictate to the community; it is the community, in dialogue with technical knowledge, that defines how the network should be organized.

The second component was the construction of a community economic model. Since 2023, the LPML has worked together with the Laboratory of Economic and Social Innovation (LAINES) at the Ibero-American University of Puebla to develop a cooperative economic framework that had proven effective in Xochiteopan. The logic is simple yet powerful: a network can only be sustained if those who use it are also those who govern and finance it. Instead of depending on external subsidies or donations, the model proposes systems of community contributions that cover operating and maintenance costs, participatory workshops in basic accounting that allow everyone to understand income and expenses, and the reinvestment of surpluses—when they exist—into strengthening the network or supporting related community projects. In Amazonian territories, low population density does not allow for large economic surpluses, but the analysis carried out showed that it is indeed possible to achieve a balance that significantly reduces individual internet access costs, transforming them into a collective expense managed with transparency. The value of this model does not lie in profitability, but in its ability to sustain economic autonomy and reinforce social cohesion around a common good.

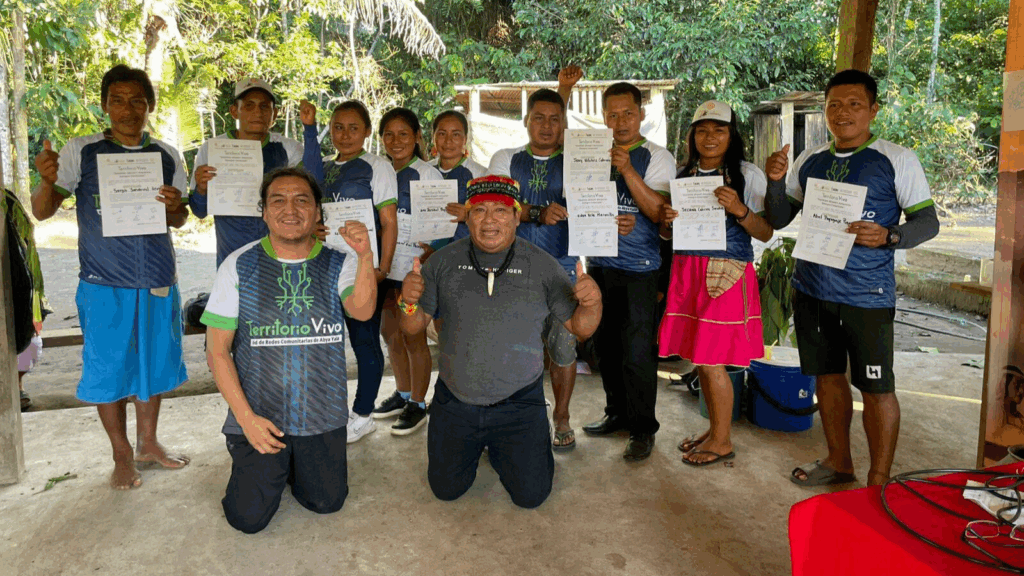

The third component was the pedagogical process. The LPML designed a training itinerary that recognized different levels of experience among participants. The category of junior technicians was established, responsible for the basic operation of local nodes and initial maintenance, as well as that of advanced technicians, in charge of network expansion, long-range link configuration, and training new members. This differentiation did not respond to a hierarchical logic but to the need to acknowledge diverse learning paths and create progressive routes of capacity building. The methodology adopted was inspired by Freirean popular education, structured in the cycle of reflection–action–reflection. In the first stage, horizontal dialogue spaces were promoted where participants shared their experiences and challenges. From there, real practices of installation, equipment configuration, content production, and exercises in economic sustainability were carried out. Finally, a collective critical reflection space was opened in which results were evaluated, errors discussed, and improvements proposed. The outcome was a participatory and emancipatory pedagogy, where knowledge was not transmitted unidirectionally but generated collectively, rooted in territorial experience.

The pedagogical process was not limited to in-person training. A key component was the creation of a digital technical-sharing space through a collaborative chat, complemented by online support sessions. In these spaces, junior and advanced administrators could raise questions, share configurations, send screenshots of errors, and receive immediate feedback from peers and facilitators. This dynamic generated continuous support that went beyond the duration of face-to-face workshops, creating a community of practice that persisted beyond the training schedule. This type of pedagogical process, which includes methodologies developed by the LPML in collaboration with international actors such as WITNESS since 2018, draws not only on Freirean pedagogy but also on the Laboratory’s accumulated expertise in technical and narrative training schools such as CORAL and Escuela Común.

The impacts of Sianëtsio sikowa’i “Amazonía Siempre Conectada” are expressed across multiple dimensions. Socially, connectivity strengthened the autonomy of the Siekopaai Nation by improving internal communication, expanding access to educational and health information, and consolidating territorial organization. Economically, the community model reduced costs and established a sustainable self-management scheme. Pedagogically, the training of local technicians ensured system continuity and opened the possibility of future expansion. Politically, the project stands as a concrete example of digital sovereignty, where technological infrastructure is not an external service but a tool for the defense of territory and culture. Community internet should not be understood as just another service, but as a process of autonomy and organization that transforms community life and strengthens the capacity of peoples to decide their own future.

Amazonía Siempre Conectada confirms that the digital future of peoples cannot be built from the outside, but from within, recognizing the richness of their cultures and the strength of their organization. Today, the Siekopaai Nation has communication tools that not only link computers and phones, but also connect struggles, memories, and collective dreams. In the forest, among rivers and ancient trees, invisible networks are now also being woven that sustain life and autonomy.

Laboratorio Popular de Medios Libres

September 2025